Local couple want people to know what happened to their adopted daughter who died of a measles-related disease.

Emmalee Madeline Parker’s Indian name, Snehal, means love in Hindi.

After Erica and Brian Parker adopted Emmalee in July 2005 from an orphanage in Pune, India, they decided to keep Snehal as her second middle name — a reminder of her heritage and the love and joy she brought into their lives.

Emmalee instantly won the Parkers’ hearts with her bubbly personality and beautiful smile. On the flight home from India with her new parents, the tiny 21/2-year-old learned her first English words, “hi” and “bye.” After landing at BWI airport, Emmalee proceeded to say “hi” to everyone she saw in the airport terminal.

The Parkers took all the precautions with Emmalee that parents can take: Cutting her grapes in quarters so they weren’t a choking hazard, making sure she didn’t slip in the bathtub or fool around poolside.

Emmalee Parker dons a princess outfit while in the hospital in one of the many pictures of Emmalee the Parkers keep Brian s dental office in Hanover. (Submitted photo)

What the Parkers couldn’t foresee was a rare, incurable disease that quickly took Emmalee from their arms.

“In a million years, no parent ever envisions a rare, fatal disease from not getting a measles vaccine in this day and age,” Erica Parker said.

Information gaps

Erica and Brian Parker had moved to Littlestown from Baltimore in 2002, after Brian set up a dental practice on Stock Street in Hanover. For years they had wanted to adopt a child. Through Maine Adoption Placement Service, the Parkers narrowed their search to children from India, where both had close friends.

The Parkers were asked in 2004 if they were interested in adopting a baby girl named Snehal, who was living in the Preet Mandir orphanage in Pune, a major city just east of Mumbai. They jumped at the chance.

The adoption process was long and frustrating. The Parkers received periodic updates about Emmalee’s health, which indicated she was sickly and underweight. They could do little to help her except send care packages and cross their fingers that the gifts weren’t pilfered in transit.

“Even if the child isn’t well in an orphanage in India, they stay there until all the paperwork is completed,” Erica said.

Erica and Brian Parker, of Littlestown, pose with their daughter, Emmalee, who they adopted from India. Emmalee died at the age of 8 from a rare disease related to having the measles. Her adoption agency noted she received the vaccine, and the Parkers want to do what they can to tell their daughter’s story and warn others. (Submitted photo)

“So, for the year and a half that we knew about her, being told ‘sorry she is not doing well, she’s not gaining weight, constant diehard and vomiting, failure to thrive,’ there was nothing we could do about it.”

When the Parkers traveled to India to pick up Emmalee and close the adoption, they were excited to finally hold the girl they had gotten to know through updates and pictures. The Parkers also were pleasantly surprised when orphanage officials were able to provide Emmalee’s medical information.

“When you do an international adoption there are lots of gaps in information, so if you get information about the child you’re really very lucky,” Erica said.

The documents stated that Emmalee was vaccinated for measles at 16 months old. It did not mention anything about her contracting the viral disease, which is still common in India.

“Not one word about her contracting the measles,” Erica said. “She’d been in that orphanage since 11 days old. You would have seen those measles. You would see those dots on a child.”

Doctors in America later told the Parkers they believed Emmalee was exposed to measles before she was 1, and that the disease took years to manifest itself in the form of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), an almost always fatal disease.

Not what they thought

Malnourished, Emmalee weighed only 17 pounds when the Parkers brought her home.

“She just was teeny-tiny physically, not spiritually,” said Erica, noting that all the toddler clothing they had bought for Emmalee was too big.

Soon after settling into her new home, Emmalee showed that she had behavioral issues. She was prone to screaming fits and later she had trouble with fine-motor skills such as using scissors and paste.

“Her behavior was not like many children you see. Emmalee had what appeared to be tendencies of emotional outbursts, hyperactivity and learning disabilities,” said Erica, a former teacher. “Through the years the pediatrician we were taking her to just chalked it up to ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder).”

After noticing that Emmalee had a tremor in her right hand, the Parkers took her to a pediatric neurologist. That trait was attributed to her malnutrition.

The Parkers spent years taking Emmalee to child psychiatrists for the behavioral issues and physical therapists for the tremor.

According to the Parkers, all of the specialists accepted the ADHD diagnosis.

“They don’t look any further because they assume every kid in the world who has this package of behavior must be ADHD, because all the American kids are ADHD,” Erica said.

At the same time, Emmalee was bright and intelligent, learning backgammon in kindergarten. She loved to play Uno and chess.

Emmalee had a wide smile and big brown eyes, and a birthmark on her cheek in the shape of a heart turned on its side.

“We just called it her pretty mark,” Erica said.

She loved to play on the monkey bars and was up for any kind of physical activity.

“This is a child who could run circles around most people,” said Erica, who gushes when she describes Emmalee’s personality. “This child could climb hand-over-hand at 21/2 like nobody’s business.”

Then on Aug. 7 last year, the Parkers noticed Emmalee having coordination problems. By the next morning, during Sunday breakfast, the Parkers noticed Emmalee dipping her head and listing to one side.

That Monday morning they took Emmalee to their pediatrician, who recommended she see a neurologist and have a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). But the Parkers were told they had to wait three weeks for an appointment.

With their anxiety growing, the Parkers took Emmalee to Hanover Hospital’s emergency room, where staff performed a CT scan and did blood work on her. Neither revealed anything unusual. The Parkers later learned that once SSPE is beyond the early stages, blood work would not indicate anything unusual.

That night, Erica called numerous hospitals trying to find one that would perform a pediatric sedation for an MRI. She also e-mailed friends and relatives telling them that Emmalee was ill and in need of their prayers.

Dr. Flaura Winston, a pediatric physician at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Erica’s cousin, responded by telling the Parkers to immediately come to CHOP.

A team of physicians, including doctors originally from India, was waiting for them.

“They looked at her, and they looked at Brian, and they looked at me, and their faces changed,” Erica said.

The doctors kept asking her when Emmalee had had measles.

“I said ‘measles, what are you asking about measles for? I’m here because my daughter is falling down,'” Erica recalled.

Emmalee stayed a week in Children’s Hospital as doctors performed various tests. When the results came back, the Parkers and Erica’s mother were called to a meeting with more than 20 doctors.

The Parkers could tell that it was bad news as soon as they entered the room.

“Many doctors who didn’t seem to want to make eye contact,” Erica added.

They were told that Emmalee had SSPE, a rare progressive encephalitis caused by persistent infection of immune-resistant measles. Doctors told them the disease was fatal and patients could live one to three years or could die in as little as three months after diagnosis.

“We all felt like a ton of bricks had dropped on us,” Brian said. “We were completely stunned.

“I had never heard of this disease.”

According to Dr. Sudha Kilaru Kessler, neurologist and one of Emmalee’s doctors, the disease is so rare that most American doctors would not know to look for it. Kessler knows of only two cases of the disease at CHOP, including Emmalee, and both were born outside the United States.

“The Indian doctors (at Philadelphia) knew,” Brian said. “Because they knew about it, they knew this was actually stage two of four stages of SSPE … falling down a lot and not being aware of it.”

The next day, Emmalee was released from the hospital and the Parkers headed home, struggling to not let on to Emmalee about the seriousness of her condition.

“It’s a very long ride from Philadelphia to Littlestown with a child that you know is terminally ill,” Erica said.

Devastated, the Parkers immediately began making calls and doing research.

Doctors were treating Emmalee with a series of anticonvulsants, and interferon to bolster her immune system. They hoped to at least slow the disease’s progression.

One of the world’s leading experts on treating SSPE patients, Dr. Banu Anlar, advised Emmalee’s doctors on immunivir, which has been shown to slow the disease in about 30 percent of SSPE patients.

“Some patients appear to benefit from the medications, some improve spontaneously, but many others unfortunately get worse,” Anlar said.

But the drug is not approved for sale in the United States, and Erica tracked down a firm in Ireland that produces immunivir, and had it shipped to Canada before it could be sent to Emmalee’s doctors.

“We were doing a lot of research, going to the doctors with e-mails and calling, trying to get some sort of treatment that had a better chance of success than what she was on,” said Brian, whose office is dotted with pictures of his daughter.

‘Wobbly woopsies’

The Parkers tried to keep their spirits up.

And Emmalee never lost her outgoing, friendly nature, despite weekly trips to Hanover Hospital for blood work and seizures that would cause her limbs to jerk and her body to lurch.

“We called it the ‘wobbly woopsies,'” Erica said.

Meanwhile, Erica met with Emmalee’s team of assistants and teachers as she prepared to enter second grade at Rolling Acres Elementary in Littlestown.

Emmalee was not the same child that completed first grade a few months earlier.

“There were lots of noticeable changes in her memory. She had forgotten a lot of her academic skills,” Erica said. “I told them ‘I can’t tell you Emma will make it through second grade.'”

Trisha Reed, assistant principal at Rolling Acres, said Emmalee’s personality shined through her disabilities, especially in her interaction with others.

Other students bonded around Emmalee she recalled: “If she needed anything, they were right there making sure she was cared for.”

The Parkers also made regular trips to the Children’s Hospital as doctors tried various combinations of medicines to get Emmalee’s seizures under control. They tried to make the best of their time there.

Sometimes they would go out to eat and get Emmalee’s favorites; pizza and corn on the cob. After a visit to the hospital in September, the Parkers spent the day at Sesame Place.

“She climbed and rode and jumped. She spent the whole day and wore herself out,” Erica said.

It was typical of her energetic personality that shined through her grim circumstances.

“Even though she was really sick with the seizures, she was a social butterfly,” Erica said.

Emmalee’s physical condition deteriorated. Her head drops became more severe. The Parkers had to hold her head up to help her eat and padded her with pillows.

Then, in late October and early November, the combination of medicines seemed to offer the Parkers encouragement.

“We thought this is great, she is seeming stable, maybe she could go for years,” Brian said. “There is one kid who has survived for 10 years.”

“Even the teachers said, ‘Gee, she’s like the old Emmalee,’ ” Erica said.

But it wasn’t long before her condition deteriorated again.

The Parkers ended up back in Philadelphia on the Wednesday before Thanksgiving. Another battery of tests there revealed that Emmalee had developed ADEM (acute disseminated encephalomyelitis), an infection on top of her encephalitis.

“This time they found major brain damage, very bad changes in the brain,” Erica said.

The Saturday after Thanksgiving, Emmalee developed severe seizures and her vital signs dropped. She no longer recognized her parents.

“They’ve got her on all these different seizure medicines and nothing is controlling the seizures,” Erica said.

A last-ditch attempt to stop the seizures was to give her steroids. There was a brief respite before Emmalee slipped into a coma.

“She never woke up again,” said Erica, her voice breaking.

The Parkers left Children’s Hospital for the last time on Dec. 7, Emmalee’s eighth birthday. The hospital offered an ambulance but the Parkers insisted on taking her home in the family van.

“Here we are with an unconscious child in our van, for her last ride home, bringing her home for hospice because of this disease we didn’t know about until August,” Erica said.

Erica’s mother and VNA Hospice helped the Parkers care for Emmalee after she returned home. It was a bleak time, waiting for the inevitable. Erica would sometimes place a stuffed animal on Emmalee’s stomach so she could tell the girl was still breathing.

But on Jan. 2, Emmalee breathed her last breath.

Telling her story

The Parkers are left with warm memories of their beautiful child and frustrations over how her condition slipped through the cracks.

They are upset that the orphanage, which has since been shut down, did not document Emmalee’s early exposure to measles. They are frustrated that doctors and therapists here didn’t recognize SSPE earlier. They are frustrated in a medical system that required them to obtain one of the medicines Emmalee needed from outside the country.

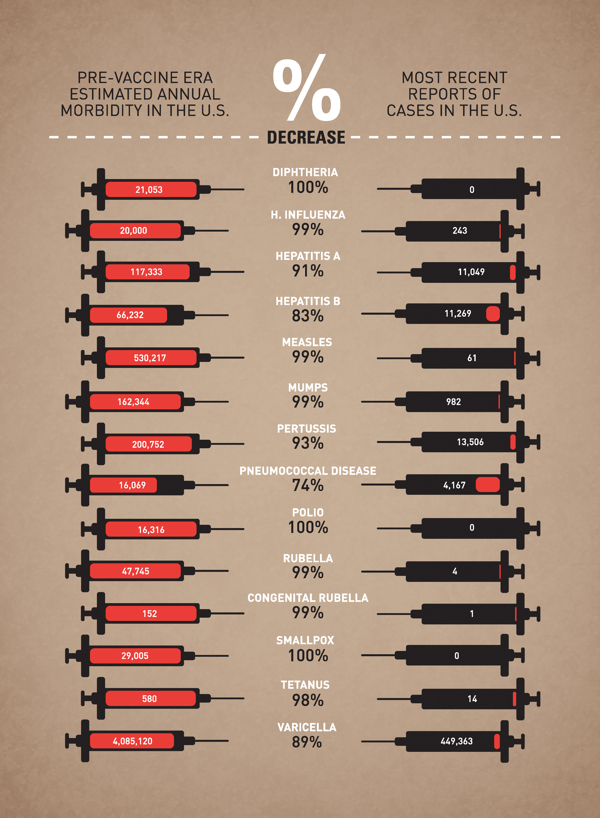

Despite her pain, and because of it, Erica Parker eagerly tells Emmalee’s story. She is determined to make other adopting parents aware of SSPE and other diseases that foreign children might have. She is determined to make sure parents know of the importance of getting their children vaccinated for measles.

“I want people to know it can happen to their adopted child. I want them to know this could happen to their biological child,” Erica said. “If you don’t vaccinate, you are playing Russian roulette not only with your kid but with the kid who might be sick sitting next to them.

“Most people say, ‘Oh we got rid of measles.’ Well, no we didn’t. Internationally adopted kids are getting it and other people are able to get it as well. It’s not a third-world-country disease,” she said.

Erica advocates for parents to push for second opinions.

“No parent should end up with an adopted child with an illness like this undiagnosed for years because nobody knows,” she said.

Most of all, the Parkers want Emmalee to be remembered for her lively spirit and beautiful personality.

“I don’t want Emmalee to be a statistic,” Erica said. “I want her to be remembered and people say ‘wow she was the most active, lively, social child.’

“She kept going until she couldn’t go anymore.”